NEURENICA. NEUROBIRTH OF VENUS

The title Neurenika is a deliberate yet subtle linguistic and conceptual play that resonates on multiple levels with Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. This similarity is not merely phonetic—it carries a series of deeper intertextual and semantic references that can be read as a conscious artistic strategy.

Here is a synthetic analysis of these connections:

-

Phonetic and rhythmic resemblance Neurenika rhythmically and phonetically echoes Guernica—three syllables, ending in “-ika,” with a hard stress in the middle. This phonetic echo immediately evokes Picasso’s masterpiece, placing the work within the orbit of engaged, symbolic art with high emotional and political charge.

-

Symbolic shift of theme: from external war to internal war Guernica is an icon of resistance against war, violence, and totalitarianism. Neurenika transfers this rebellious gesture to the terrain of individual identity—an internal, existential, bodily war. Instead of the collective suffering of a city bombed by fascists, we witness a neuronal and emotional zone of conflict: tension between biology, societal expectations, and personal truth of existence. The prefix “neuro-” (or “neuren-” as a neologism) suggests a mental, psychological, technological dimension, while also referring to neuroplasticity and neuro-transformation—concepts central to reflections on identity in the age of transhumanism.

-

Aesthetics of trauma Guernica is an image of national trauma. Neurenika is a trauma of the body, society, culture, and transformation. Both works employ an aesthetics of rupture: deconstructed space, exaggeration, contrast, and bodily symbolism. In Neurenika, the layered and fragmented aesthetics of the digital image becomes a new language for representing posthuman trauma, where the subject no longer seeks wholeness but reconciles with its complexity.

-

Political charge of the title Both Guernica and Neurenika are political titles—not only socially but existentially. Guernica is an indictment of fascism; Neurenika is an indictment of normative systems, binary gender structures, ideologies of the body, and imposed identity. In this sense, Neurenika is a digital manifesto of resistance, rooted in the tradition of engaged art yet operating in the language of new media and intimate narrative.

-

Crisis of iconicity Guernica is a classic 20th-century icon. Neurenika can be read as a deconstruction of the icon—an attempt to inscribe a contemporary image into the iconoclastic field: not as a unified representation but as a palimpsest, fragment, fluid sign of an era of fluid identity. The title thus signals an aspiration toward a new iconicity, rooted in body politics, networks, and posthuman subjectivity.

Summary:

The title Neurenika is a strategic and meaningful neologism that:

- phonetically invokes Guernica,

- thematically shifts the focus from political war to identity war,

- points to new types of trauma—somatic, social, post-binary,

- situating itself in postmedial and cyberfeminist currents, poses the question of new images of protest and memory.

The particle “neuro-” in Neurobirth of Venus functions as a key semantic and philosophical marker, anchoring the work in the context of contemporary transformations of identity, corporeality, and the relationship between body, mind, and technology. This neologism — a wordplay combining “birth” with “neuro” — opens multiple interpretive levels.

-

“Neuro-” as a sign of internal and cognitive transformation Unlike the classical Birth of Venus, where transformation concerns bodily revelation and ideal beauty, Neurobirth of Venus suggests birth on the level of neurons, consciousness, and psychic identity. This is not biological coming-into-being but a process of mental and emotional re-configuration. In this sense, Venus—the traditional figure of the feminine ideal—becomes a post-neuronal persona: the result of dialogue between mind, technology, pharmacology, and social narrative.

-

Neuro as a dimension of posthuman identity The “neuro-” particle also refers to the broader aesthetics of posthumanism and neurohumanities, where the body is no longer the autonomous foundation of identity but a system subject to constant change—both biological (e.g., hormonal) and digital (imagistic, medial, narrative). Neurobirth of Venus is thus a metaphor for the birth of the subject as a configuration of neurological, hormonal, and cultural data—continuously processed and reconstructed.

-

Neuro as a trace of trauma and reprogramming In a transgender and transformative context, “neuro-” also carries the potential for narratives of trauma, neuroplasticity, and adaptation. The process of gender and sex change is also a profound rewiring—not only of the body but of perception, emotions, and social relations. The “neuro-” particle thus points to an internal revolution—difficult, painful, yet creative. Such “births” are not a one-time act but a continuous state of neuro-emotional metamorphosis.

-

Media context: neuro- as a medial and aesthetic concept “Neuro-” is also a keyword in modern discourse on technology and media—neurointerfaces, neuromarketing, neuroaesthetics. In this sense, the title Neurobirth of Venus can be read as a commentary on the aesthetics of an era of sensory overload and algorithms, where identity and body are constantly constructed through media—stimulated, optimized, simulated. Venus, born not from sea foam but from neuronal impulses and digital processing, becomes an icon of new synthetic corporeality.

-

Irony and deconstruction of the myth of beauty Adding “neuro-” to “birth of Venus” destabilizes the classical myth of beauty. Instead of a divine, natural Venus, we have a constructed, composite, neurochemical, and cultural figure. This is an ironic, post-digital gesture in which neurobiology and technological transgression unmask the mythology of the body as the essence of femininity, proposing instead a body as palimpsest—multilayered, multilingual, ambiguous.

Summary:

The “neuro-” particle in Neurobirth of Venus:

- shifts the dimension of birth from body to mind and technology;

- signals bodily transformation as a neuropsychic and cultural act;

- anchors the work in posthumanist and cyberfeminist currents;

- decodes the myth of beauty in light of contemporary identity tensions;

- finally, creates a new icon of the neuronal era—Venus as a construct of consciousness, not merely body.

The technology of creating layered post-photographic images, such as the deep-structure digital composite, perfectly fits Marshall McLuhan’s reflections in his seminal works The Medium is the Message and The Medium is the Massage. In McLuhan’s spirit, not only the content of the image but the very form and technology of its creation become the message—reorganizing our perceptual and cognitive frameworks. The digital image, built from dozens (or even hundreds) of layers, is no longer a representation of reality but a medial event that reveals the structure and rhythm of contemporary image culture: accelerated, modular, ephemeral, and obsessively complex. McLuhan predicted that every new medium does not merely extend the senses but reorganizes consciousness itself.

The post-photographic composite image—like Neurenika. Neurobirth of Venus—becomes a constantly re-configured field of meanings, where form (layered, hybrid, revealed) speaks more about the condition of contemporary identity than the theme itself. In this sense, the medium ceases to be transparent—it becomes a tangible part of the message, just as retouching, masking, blending modes, or pixels: all communicate something essential about a world that has long ceased to be unambiguous, stable, and binary.

In the spirit of McLuhan’s maxim that “the medium is the message,” the artist operates not only with content—transgressive, political, corporeal—but above all with form, which becomes voice and gesture inscribed in the space of the posthuman medial ecosystem. The post-photographic digital image, built from layers of photography, graphics, textures, and encoded narrative, functions here as a performative field—not only showing but also shaping identity, corporeality, relation to technology, and gender.

In this perspective, moRgan B. Konopka emerges as a new-type cyberfeminist—not only commenting on the effects of digital revolution but actively constructing new models of resistance and subjectivity in the media landscape. Her practice is an act of aesthetic and political intervention, inscribed in the electronic text of culture, where the subject—female, transgressive, non-binary—is extracted from the background, denied binary transparency, and presented in sharp, unnatural, consciously constructed form.

Cyberfeminism, which emerged in the 1990s as a radical response to male-centric paradigms of technology and digital narratives, finds here its current and expanded dimension. Operating at the intersection of art, technology, and queer theory, the artist not only continues the tradition of VNS Matrix or Sadie Plant but brings to it the dimension of personal, autobiographical experience of bodily transformation.

The image becomes a medial operation of identity, parallel to somatic processes of gender change, deconstruction of social roles, and transgression of binary boundaries of sex and body. Thus understood, the work fits into the posthumanist turn in art, where boundaries between medium and body, nature and technology, biology and code are radically questioned. Neurobirth of Venus is not only a reinterpretation of the Renaissance myth but also an aesthetic manifesto of the post-human era: hybrid, complicated, unstable—yet paradoxically deeply rooted in the humanist gesture of seeking meaning, beauty, and endurance.

Visual description

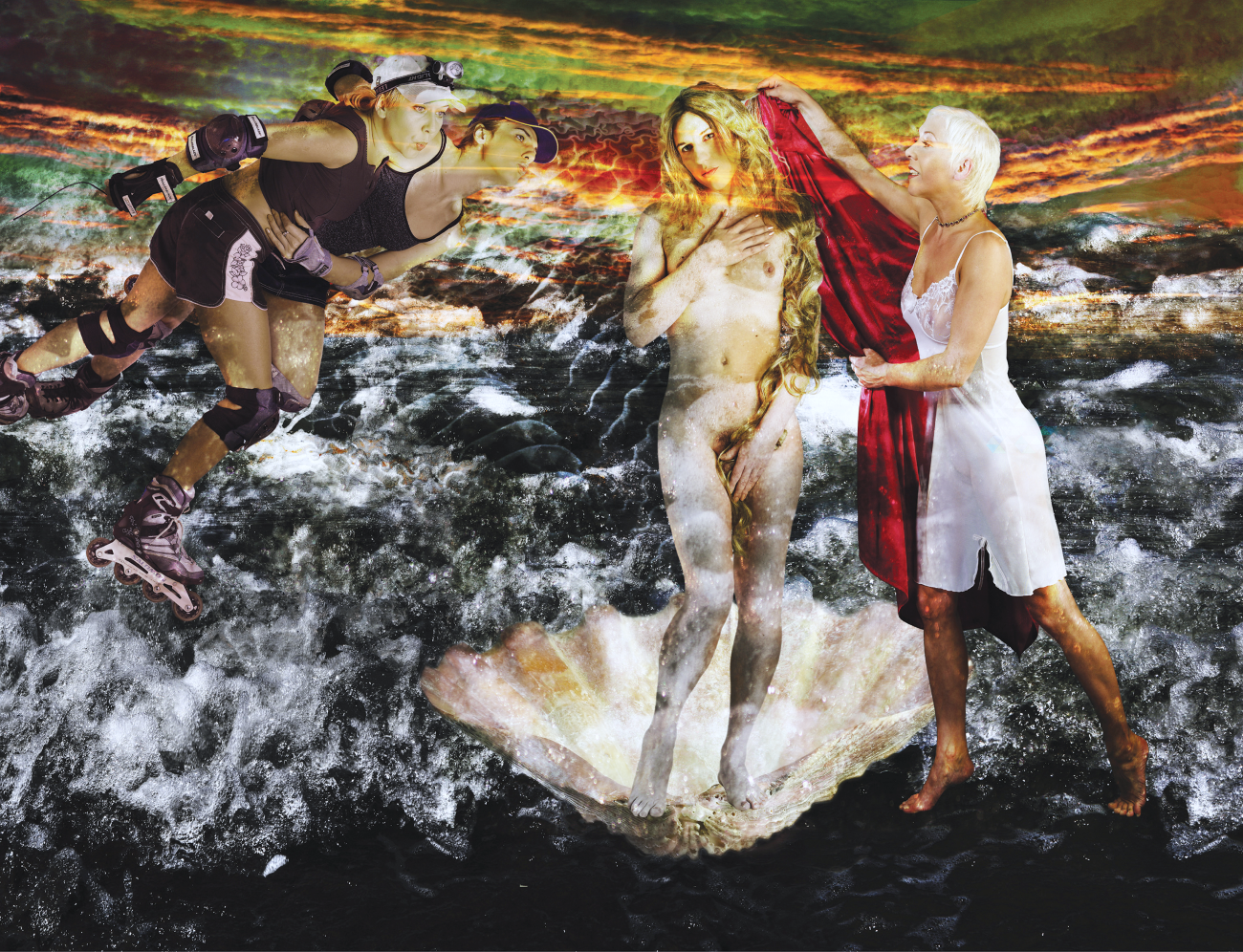

The image, created as a layered digital composite built from over 80 overlapping planes of image, texture, and color, does not aspire to illusionistic realism or a unified visual code. On the contrary—the structure of the work, based on contrasting components—from documentary photography through computer graphics to digital manipulations—exposes the complexity of the identity act and its fragmentariness.

The conscious lack of “blending” the figures into the new background is not a technical oversight but a formal gesture: revelation of processuality, discontinuity, and the performative character of transformation. The central figure—Venus—stands naked on the shell, a classic reference to Botticelli. Her body, though close to the canonical form, contains subtle features of a transgender person undergoing hormone therapy: delicate facial structure, breasts in development, no genital surgery. She covers herself with hair and hand in the classic pose.

To the right, a woman in a white slip with a smile and tenderness drapes a red fabric over Venus, evoking both a caring gesture and a symbolic act of “recognition” of Venus. To the left—two women on roller skates in modern, sporty attire—dynamically gliding with headlamps, as if from a completely different temporal dimension. Their presence seems disruptive yet vigilant, almost protective.

The background is a stormy, surreal sea and apocalyptic sky—colors are vivid, unrealistic, almost cosmic. The waves are digitally enhanced, almost abstract.

Levels of reading and symbolism

-

Identity and transformation

- Venus, the icon of feminine beauty, is shown here as a transgender person in the process of becoming.

- The shell—symbol of birth—becomes a symbol of second birth, transformation not only bodily but social.

- The red fabric may be a symbol of dignity, acceptance, covering, but also transformation—“red carpet” of new identity.

-

Collision of classic and modern

- The roller-skaters with headlamps resemble guardians, goddesses of modernity, or futuristic “sighs of the wind” from Botticelli’s original.

- Their gear and posture suggest speed, vigilance, modernity, contrasting with Venus’s classical calm.

- This collision may represent changing roles of femininity and gender in the digital, technological world.

-

Queer art, affirmation, and ritual

- The image has the character of a gender affirmation ritual—festive, solemn, visually theatrical.

- The woman covering Venus becomes a maternal, perhaps spiritual figure—the act of covering is a symbol of acceptance and “anointing.”

Style and technique – layers of formal meanings Digital/composite style

- The post-photographic image is the result of work composed of approx. 80 layers—post-photographic composite technique resembling both digital painting and collage. The layering refers to classical painting, where layering and glazing are key to achieving depth both chromatic and semantic.

- Juxtaposing realistic figures with unrealistic background builds a world on the border of dream, myth, and contemporary intervention.

- Conscious use of overexposures, overlays, and unnatural colors creates a hyper-reality effect.

Large format (250 x 190 cm)

- The size of the work indicates the intention to monumentalize the theme—Venus as a contemporary icon of emancipation and queer affirmation.

- Painterly format transferred to photography, but with strong painterly character.

Meaning of the title (presumably: “Neurobirth of Venus”) If the title is indeed “Neurobirth of Venus” (wordplay: “new birth” + “neurons,” today used in “neurodiversity”), it may refer to:

- reprogramming of identity (neuroplasticity as metaphor),

- birth of femininity in mind and body,

- transgression of social norms—birth of a new paradigm of femininity.

Summary – possible readings

| Level | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Cultural | Revision of classical patterns of beauty and gender |

| Social | Support for trans identity, affirmation, sisterhood |

| Aesthetic | Hyperrealistic, digital reinterpretation of Renaissance composition |

| Symbolic | Transformation, ritual, acceptance, birth of a new person |

| Emotional | Mixture of tenderness, tension, courage, and celebration |

“Neurenika. Neurobirth of Venus” (2006/2007)

Technique: large-format laser-exposed photography on metallic paper, 250 x 125 cm, under plexiglass on dibond In her monumental post-photographic composite image Neurenika. Neurobirth of Venus, the artist reaches for one of the most recognizable depictions of femininity in art history—Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus—to transform it into a manifesto of identity, corporeality, and transformation. The composition, made of over 80 digital layers, shows not only a clash of aesthetics but also of epochs, worldviews, and emotions. The central figure—Venus—is a transgender person undergoing hormonal therapy. Standing naked on the shell in the classic pose, she reveals her body in a transitional state: imperfect in the eyes of the normative canon yet true and affirmed. Her presence on the shell means not only the birth of femininity—it is the birth of new subjectivity: corporeal, psychic, social. The female figures accompanying Venus create a dissonant choir: on one side, contemporary roller-skaters—like techno-muses—race through the frame with headlamps, heralding transformation; on the other—a woman in a white slip tenderly covers Venus with red fabric in an act reminiscent of both maternal care and an initiation ritual. This gesture is symbolic “anointing,” affirmation of transformation occurring not only in the body but in cultural narratives. The background—stormy waves and a sky illuminated by surreal light—gives the scene an apocalyptic-mystical dimension. The space is no longer realistic: it is a landscape of the mind, an inner ocean of emotions and tensions through which a new “self” breaks through. The title Neurobirth of Venus is a multilayered wordplay: it combines “birth” with “neuro-,” suggesting self-reprogramming, psychic and social rebirth, and neurodivergent sensitivity that does not fit simple gender or cultural binaries. The work was created in 2006/2007—long before the mainstream visibility of trans people in art and public debate—and today can be read as a prophetic image of an era of transition. The artist not only reconstructs the canon but deconstructs and rewrites it anew, with full tenderness and strength.

“In this Venus, it’s not about who she was—but who she can become when we allow her to be born again. Not only from sea foam, but from recognition, empathy, and the courage to be herself.” – fragment of curatorial statement

Brief description: Neurenika. Neurobirth of Venus 2006/2007, laser-exposed photography, under plexiglass on dibond, 250 × 190 cm In this reinterpretation of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, the classical icon of femininity is rewritten as a figure of a transgender person in transformation. The artist creates a contemporary myth—intimate yet political—about a body reborn not from foam but from the courage to be oneself. Composed of over 80 digital layers, the composition juxtaposes Renaissance aesthetics with the visual language of the future: sporty roller-skaters, apocalyptic background, digitally processed waves. The women present—tender, strong, dynamic—support Venus in a symbolic ritual of transformation. Neurobirth is more than new birth. It is a story of self-reprogramming—neuroplastic, corporeal, social. About being “outside the frame” and simultaneously—fully visible.

Formal and technical analysis Composition and format

- The image is a vertical rectangle of large format (250 × 125 cm), enhancing the monumentality of the scene and evoking the tradition of historical, sacred, or allegorical painting.

- The composition is central and balanced, modeled on Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, but with clearly shifted dynamics: Venus is no longer a passive object but a subject in the act of transformation.

Digital technique – layering and montage

- The image is built from over 80 digital layers—photographic, textural, chromatic—creating an aesthetics of conscious multilayering reminiscent of both collage and digital painting and other new graphic techniques (there was no AI yet).

- Each element (figure, background, water, sky) has a visibly separate visual identity. Instead of striving for full illusion of spatial unity, the artist exposes the boundaries of joining, constituting one of the most important formal gestures of this work.

Lack of “blending” effect – significant artistic device The absence of illusion of integration (e.g., through shadow, color balance, lighting conditions) is a conscious departure from classical photomontage principles, where naturalness is often sought. Instead:

- Figures “stand out” from the background, as if cut from another order—visually resembling theatricality or quotation.

-

The corporeality of Venus, the roller-skaters, and the woman with red fabric retains its artificiality, which:

- emphasizes the constructedness of gender, its “assembly” from social, biological, technological elements;

- interrupts the illusion of “naturalness” of the body as unchanging, coherent, unambiguous.

Technical unnaturalness = metaphor of transformation

- Lack of photorealistic integration is a rejection of binary “order of nature”—woman ≠ woman in Botticelli.

- This is not an illusion of Venus’s birth but its deconstruction in the process of digital and corporeal engineering.

- The image reveals the very process of “assembling” identity—as if saying: this body, this myth, this femininity—are mounted, but no less true.

Aesthetics of syntheticity as the philosophy of the work

✂️ Digitality and “visibility of montage”:

- Presence of clear contours, artificial light, oversaturated colors, and digital textures distances the work from realism aesthetics.

- This gesture refers to the performative dimension of gender identity (Judith Butler), where “woman” is not essence but act, construct, manifesto. ? Layers as psychological and technological metaphor:

- The image becomes a field of complex overlays: biology, identity, social roles, self-vision, and body image.

- Just as every layer in Photoshop can be modified, so every layer of our identity is subject to negotiation—what is digital becomes existential here.

Summary – significance of formal devices

| Formal device | Artistic-conceptual meaning |

|---|---|

| Lack of blending figures into background | Emphasis on artificiality and constructedness of gender identity |

| Juxtaposition of classical and digital | Critique of aesthetic and social canons concerning body and femininity |

| Visible layering | Metaphor of psychic and corporeal complexity—body as montage, not essence |

| Exaggerated colors and light | Transfer of the work into the realm of myth, performance, post-natural representation |

| Unnatural perspective | Breaking the illusion of the “real world”—creation of symbolic, internal, transformative space |

Cultural background. Durability and fragility of the canon Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus has for centuries been an emblematic depiction of Renaissance ideal of beauty and harmony. In Neurobirth of Venus, the artist undertakes a conscious dialogue with this canon, turning toward the durability of identity foundations in an era of fluid gender categories and posthuman redefinitions of the body. The image, created from over 80 digital layers, becomes a starting point for reflection on how contemporary trans, queer, and posthuman currents dismantle and reassemble classical myths about the human subject.

-

Historical-artistic context of reinterpretation

- The Renaissance movement sought to recreate cosmic order in macro- and microcosm—hence Botticelli, showing Venus in ideal proportions, inscribed man in the harmony of geometry and divine order.

- Modernism and postmodernism, following Giorgio Agamben or Hans Belting, shattered this identification in favor of deconstructing myths and dispersing the subject. Their heirs in queer and posthumanist currents (Donna Haraway, Rosi Braidotti) go further: identity is no longer a “text to be read” but a process—a palimpsest that never reaches final form. In this perspective, Neurobirth of Venus functions as an artistic point of nihility and new choice: around the classical shell—symbol of fundamental order—gather contemporary, digital, performative elements.

-

Formal tools of deconstruction 2.1 Multilayering and digital collage

- Layers of photography, graphics, textures, and color filters do not aim for illusion of homogeneous space but expose the “montage” process—like Jacques Derrida pointing to traces of editing and text margins.

- Each layer corresponds to a different register: biological (Venus’s body during therapy), technological (roller-skaters with headlamps as hybrid futuristic figures), social (woman with red fabric as caring ritualist).

-

2.2 Cutting figures from the background

- Conscious lack of blending figures into the background is the antonym of “blind photorealism.” This artistic gesture emphasizes the “artificiality” of identity—recalling Judith Butler and her concept of performativity: femininity is an act, not essence.

- The visible boundary between figure and landscape is a postulate: let us not try to hide that the body is a cultural construct and that every identity bears marks of technology, normative expectations, and politics.

-

Trans and posthuman vicissitudes of the subject

3.1 Transgression of binarity

- A transgender person in the central role emblematically undermines dichotomies nature–culture and masculinity–femininity. The ritual of “covering” Venus with red fabric becomes symbolic “anointing” of a new gender position, aiming at the pragmatics of recognition in public and private spheres.

-

3.2 Posthuman dispersion

- Water and sky—oversaturated, almost alien—create an environment where the subject is not the center of the universe but an element of multiplicity: an ecosystem of quotations and fragments.

- Referring to Donna Haraway and her idea of the “cyborg,” the image asks: in the era of biotechnology, networks, and media, who are we if our body is as plastic as a pixel?

-

Renaissance foundation versus fluid modernity The vertical silhouette of Venus—though seemingly resting on the “foundation” of the shell and tradition—in fact constantly emerges and disappears. This paradox of “durable foundation in unstable reality” fits into a long line of philosophical and theological searches: from Plato through the Renaissance to the present. In Neurobirth of Venus, the foundation is no longer the canon of beauty but the process of transformation—emphasizing that identity has no single point of support but is stretched between many perspectives.

Conclusion: The image as a manifesto of new mythology Neurobirth of Venus does not attempt to restore Botticellian harmony; on the contrary—it creates a new myth in which body, gender, and human subject are a layered construct, constantly negotiated and performed. The lack of blending and visible digital architecture become aesthetic and conceptual postulates: to understand contemporary identity, we must accept its syntheticity, its motor traces, and its necessity to return to the process of “birth” anew—each time by different means.

Neurenika. Neurobirth of Venus is a call to look at transformation not as a defect but as a constant, ritual practice of creating oneself, in a space where art, technology, and gender theories meet in ceaseless dialogue.